-

Table of Contents

The Long-Term Effects of Injectable Metenolone Enanthate in Athletes

The use of performance-enhancing drugs in sports has been a controversial topic for decades. Athletes are constantly seeking ways to improve their performance and gain a competitive edge, and unfortunately, some turn to the use of illegal substances. One such substance that has gained popularity among athletes is injectable metenolone enanthate, also known as Primobolan Depot. This article will explore the long-term effects of using this drug in athletes, including its pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, and provide expert opinions on the matter.

What is Injectable Metenolone Enanthate?

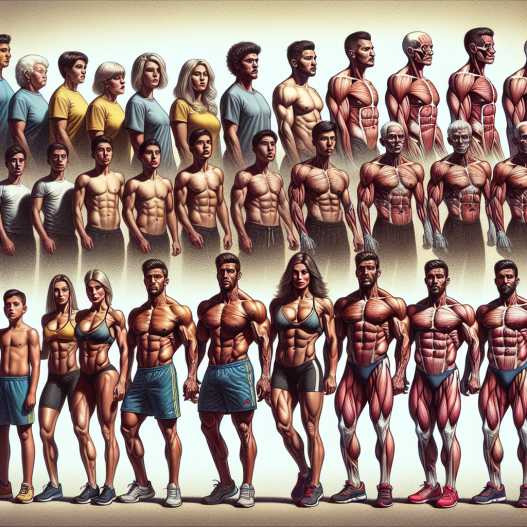

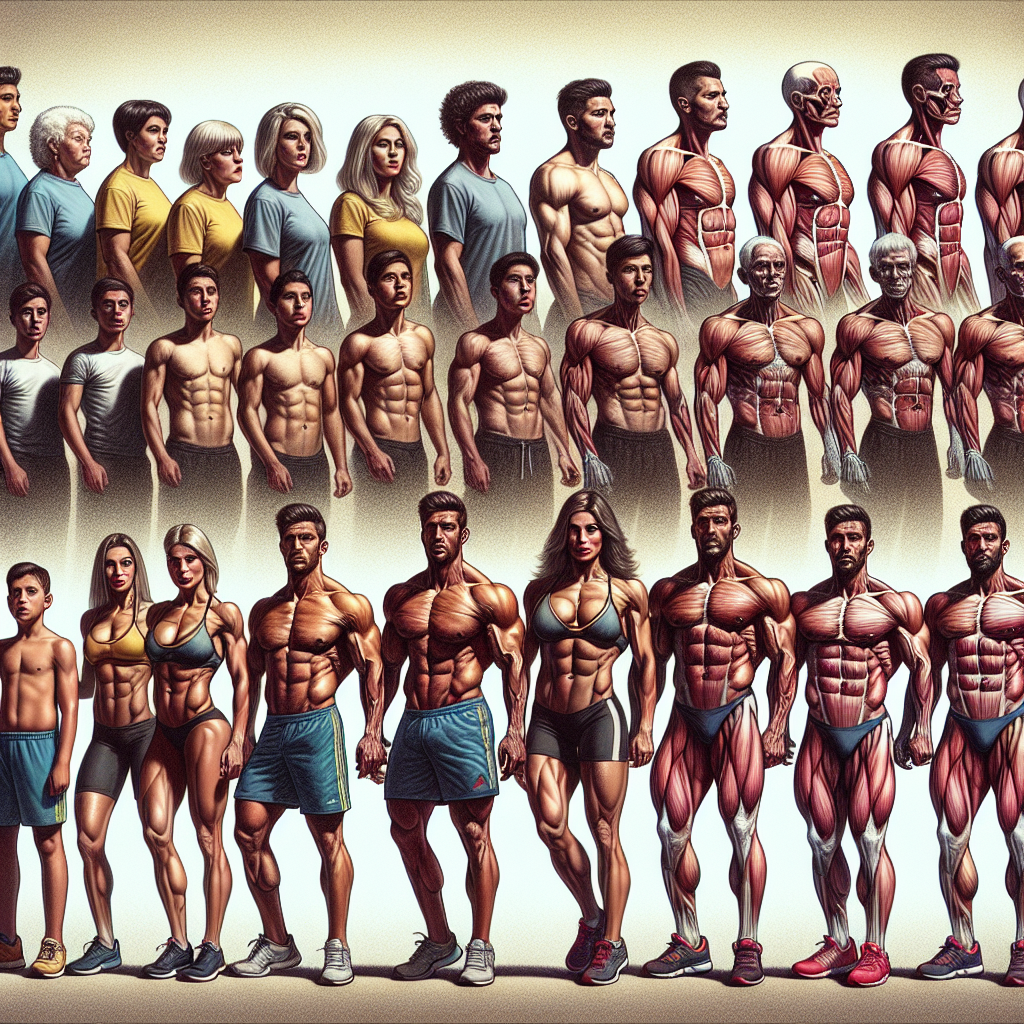

Injectable metenolone enanthate is a synthetic anabolic-androgenic steroid (AAS) that is derived from dihydrotestosterone (DHT). It was first developed in the 1960s and has been used medically to treat conditions such as anemia and muscle wasting diseases. However, it has gained popularity among athletes for its ability to increase muscle mass, strength, and endurance.

Injectable metenolone enanthate is typically administered via intramuscular injection and has a half-life of approximately 10 days. This means that it stays in the body for a longer period compared to other AAS, making it a popular choice for athletes who want to avoid frequent injections.

Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics

To understand the long-term effects of injectable metenolone enanthate, it is important to first understand its pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. The drug is metabolized in the liver and excreted through the kidneys. It has a high bioavailability, meaning that a large percentage of the drug is absorbed into the bloodstream.

Once in the body, injectable metenolone enanthate binds to androgen receptors in muscle cells, stimulating protein synthesis and promoting muscle growth. It also has a mild androgenic effect, which can lead to increased aggression and competitiveness in athletes.

Studies have shown that the use of injectable metenolone enanthate can lead to a significant increase in muscle mass and strength, with minimal side effects. However, like all AAS, it can also have negative effects on the body, especially when used in high doses or for extended periods.

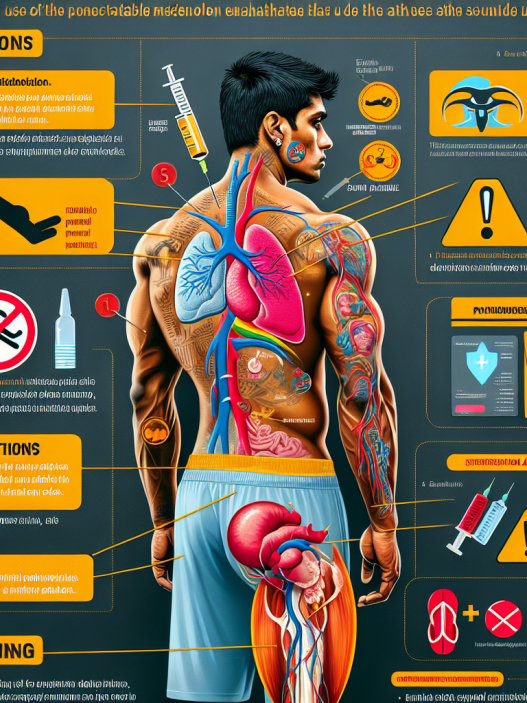

Long-Term Effects on the Body

The long-term effects of using injectable metenolone enanthate in athletes are still not fully understood, as there is limited research on the subject. However, some potential risks and side effects have been identified.

Cardiovascular Effects

One of the most concerning long-term effects of using injectable metenolone enanthate is its impact on the cardiovascular system. AAS use has been linked to an increased risk of heart disease, including high blood pressure, heart attacks, and strokes. This is due to the drug’s ability to increase red blood cell production, which can lead to thickening of the blood and strain on the heart.

In a study by Hartgens and Kuipers (2004), it was found that AAS use, including injectable metenolone enanthate, can also lead to changes in cholesterol levels, with a decrease in HDL (good) cholesterol and an increase in LDL (bad) cholesterol. This can further increase the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Hormonal Imbalances

Injectable metenolone enanthate, like other AAS, can also disrupt the body’s natural hormone balance. This can lead to a decrease in testosterone production, which can have a range of negative effects, including decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, and infertility. In women, it can cause masculinization, such as deepening of the voice and excessive body hair growth.

Furthermore, long-term use of AAS can also lead to a condition known as hypogonadism, where the body’s natural production of testosterone is permanently suppressed. This can have serious consequences for an athlete’s health and well-being.

Mental Health Effects

Another potential long-term effect of using injectable metenolone enanthate is its impact on mental health. AAS use has been linked to mood swings, aggression, and even psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety. These effects can have a significant impact on an athlete’s personal and professional life.

In a study by Pope and Katz (1994), it was found that AAS use can also lead to dependence and addiction, with users experiencing withdrawal symptoms when they stop using the drug. This highlights the potential for long-term psychological effects of AAS use.

Expert Opinions

While the long-term effects of using injectable metenolone enanthate in athletes are still being studied, experts in the field of sports pharmacology have expressed concerns about its use. Dr. Harrison Pope, a leading researcher on AAS use in athletes, has stated that “the potential risks of using AAS, including injectable metenolone enanthate, far outweigh any potential benefits.” He also emphasizes the need for more research on the long-term effects of these drugs.

Dr. Charles E. Yesalis, a professor of health policy and administration at Penn State University, has also expressed concerns about the use of AAS in sports. He states that “the use of AAS can have serious consequences for an athlete’s health and well-being, and it is important for athletes to understand the potential risks before using these substances.”

Conclusion

In conclusion, while injectable metenolone enanthate may offer short-term benefits for athletes, its long-term effects on the body can be potentially harmful. From cardiovascular risks to hormonal imbalances and mental health effects, the use of this drug can have serious consequences for an athlete’s health and well-being. It is important for athletes to understand the potential risks and to consider the long-term implications before using performance-enhancing drugs. More research is needed to fully understand the long-term effects of injectable metenolone enanthate and other AAS in athletes.

References

Hartgens, F., & Kuipers, H. (2004). Effects of androgenic-anabolic steroids in athletes. Sports Medicine, 34(8), 513-554.

Pope, H. G., & Katz, D. L. (1994). Affective and psychotic symptoms associated with anabolic steroid use. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151(4), 527-533.